It’s the worst possible scenario. You’re taking off on an asphalt runway. Normal run-up. Perfect weather. Quick takeoff clearance, but within 400 feet of rotating you hear (and feel) the engine heave. Suddenly, it has breathed its last and all is silent. You have just experienced an engine failure on takeoff. Behind you lay 5,000 feet of perfectly smooth asphalt. Will you go back? Do you attempt “the impossible turn?” The impossible turn is the emergency return to airport maneuver attempted when engine power is lost. The turn has been dubbed-” impossible”- and for good reason. Let’s look at the Aerodynamic factors involved in this maneuver.

Here are some official statements and excerpts taken from official FAA documents in regard to the ‘impossible turn’:

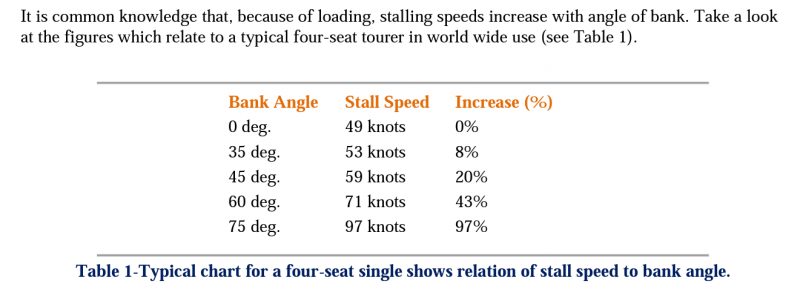

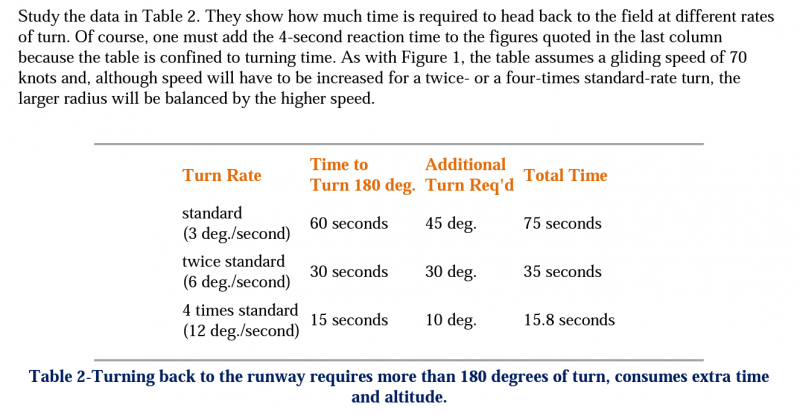

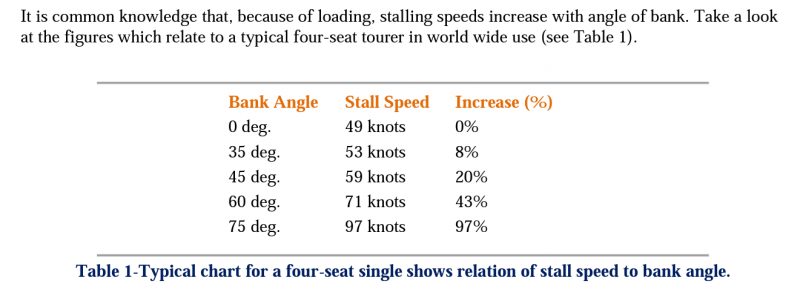

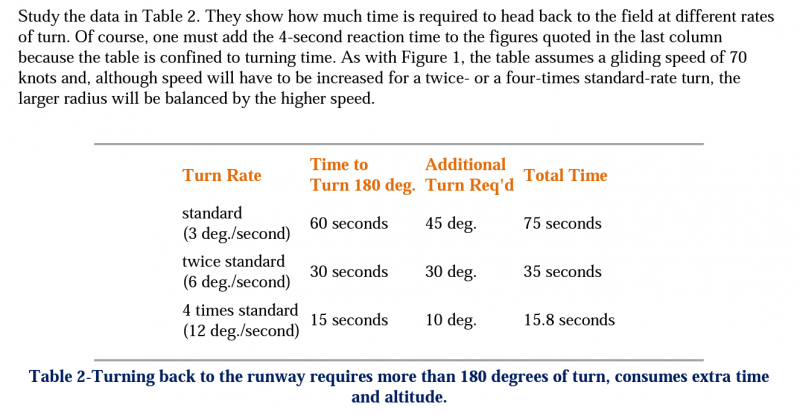

Figure 1

Figure 2

Remember the airplane stalls at an angle of attack, not an airspeed. Airplanes in sharp turns with low power can enter into an “accelerated stall.” This is how a majority of impossible turns ends – a stall/spin.

If you are below 400 feet AGL your best option is straight. Hit whatever you are going to hit as softly as possible.

If you are between 500-1,000 feet AGL the FAA and others recommend exploring at least 10-60 degrees of possible deviation ahead of you.

At or above 1,000 feet becomes a judgment call. Even at this altitude, it’s still best to keep going forward, especially if there are fields/farmlands ahead. If you are somehow able to have enough altitude to make it back to the runway, remember you will now have a tailwind on landing.

Here are two quick references checklists the FAA recommends when facing an engine failure during the take-off phase of flight, check your own aircraft for emergency procedures prescribed.

Pull out the throttle;

Brake firmly;

Maintain runway heading;

While the aircraft slows down, turn off the fuel, switch off the mags, and pull the mixture into idle cutoff to minimize fire risk;

When there is a risk of passing the runway’s end or even running off the airfield entirely, swing onto the grass. Take firm avoidance action when obstacles are present

Immediately depress the nose and trim into the glide at optimum speed;

Look through an arc of about 60 degrees left and right of the aircraft heading and select the best available landing area;

Turn off the fuel and mags. Pull the mixture to idle-cutoff to minimize fire risk;

If yours is a tailwheel aircraft, avoid the risk of turning over during the landing by retracting the gear (if applicable). It is better to leave the nose gear extended on tri-gear aircraft to absorb the first shock of arrival;

Make gentle turns to avoid obstacles;

When you are sure of reaching the chosen landing area, lower the flaps, in stages if necessary, but aim to have full flaps before touchdown. Do not allow the airspeed to increase;

On short final, turn off the master switch and unlatch the cabin doors (to guard against the risk of being trapped in the cabin through the doors jamming);

Resist the temptation to turn back to the field!

The key is to have a plan that you brief before every take-off (even if it’s just to yourself). You have to know what your options are and be ready to react properly, given the conditions. This briefing always considers a few essential things:

Runway length: when can we just land back on the runway? A 10,000 ft. runway gives you more options straight ahead

Airport environment: is there a parallel or intersecting runway that is more convenient to turn towards?

Surrounding terrain: are there any good options besides the airport or conversely, are there any obstacles to avoid?

Wind: I like to turn into the wind when possible since this requires a less aggressive turn to be lined up on final

Ceiling and visibility: do we need to set up any avionics to find our way back to the runway if it’s low IFR (synthetic vision helps a lot here)?

Lastly, we should consider that the human factor is an important piece of the puzzle, often left out during briefings. It's hard to predict how a pilot will react when faced with a serious emergency at a low altitude, but one thing is certain, your response will not be immediate. It will take you time to process the emergency, and you may even try troubleshooting (not that it's a bad idea, you should run an engine failure checklist if you have time). But, even taking a few seconds to troubleshoot could take away hundreds of feet of potential altitude. We hope this Safety Notice, will give a new insight to all pilots, and may be used towards your next flight.

Fly safe always.

The impossible turn generally refers to a low altitude, 180-degree turn back to the departure airport after experiencing an engine failure on takeoff. The classic scenario involves a sudden power loss below 1000 ft. AGL, where the pilot feels an overwhelming urge to crank and bank their way back to the safety of a runway. There’s not much margin for error, especially at low altitudes, and if it’s not done properly the result can be fatal.

It’s the worst possible scenario. You’re taking off on an asphalt runway. Normal run-up. Perfect weather. Quick takeoff clearance, but within 400 feet of rotating you hear (and feel) the engine heave. Suddenly, it has breathed its last and all is silent. You have just experienced an engine failure on takeoff. Behind you lay 5,000 feet of perfectly smooth asphalt. Will you go back? Do you attempt “the impossible turn?” The impossible turn is the emergency return to airport maneuver attempted when engine power is lost. The turn has been dubbed-” impossible”- and for good reason. Let’s look at the Aerodynamic factors involved in this maneuver.

Here are some official statements and excerpts taken from official FAA documents in regard to the ‘impossible turn’:

Figure 1

Figure 2

Remember the airplane stalls at an angle of attack, not an airspeed. Airplanes in sharp turns with low power can enter into an “accelerated stall.” This is how a majority of impossible turns ends – a stall/spin.

If you are below 400 feet AGL your best option is straight. Hit whatever you are going to hit as softly as possible.

If you are between 500-1,000 feet AGL the FAA and others recommend exploring at least 10-60 degrees of possible deviation ahead of you.

At or above 1,000 feet becomes a judgment call. Even at this altitude, it’s still best to keep going forward, especially if there are fields/farmlands ahead. If you are somehow able to have enough altitude to make it back to the runway, remember you will now have a tailwind on landing.

Here are two quick references checklists the FAA recommends when facing an engine failure during the take-off phase of flight, check your own aircraft for emergency procedures prescribed.

Pull out the throttle;

Brake firmly;

Maintain runway heading;

While the aircraft slows down, turn off the fuel, switch off the mags, and pull the mixture into idle cutoff to minimize fire risk;

When there is a risk of passing the runway’s end or even running off the airfield entirely, swing onto the grass. Take firm avoidance action when obstacles are present

Immediately depress the nose and trim into the glide at optimum speed;

Look through an arc of about 60 degrees left and right of the aircraft heading and select the best available landing area;

Turn off the fuel and mags. Pull the mixture to idle-cutoff to minimize fire risk;

If yours is a tailwheel aircraft, avoid the risk of turning over during the landing by retracting the gear (if applicable). It is better to leave the nose gear extended on tri-gear aircraft to absorb the first shock of arrival;

Make gentle turns to avoid obstacles;

When you are sure of reaching the chosen landing area, lower the flaps, in stages if necessary, but aim to have full flaps before touchdown. Do not allow the airspeed to increase;

On short final, turn off the master switch and unlatch the cabin doors (to guard against the risk of being trapped in the cabin through the doors jamming);

Resist the temptation to turn back to the field!

The key is to have a plan that you brief before every take-off (even if it’s just to yourself). You have to know what your options are and be ready to react properly, given the conditions. This briefing always considers a few essential things:

Runway length: when can we just land back on the runway? A 10,000 ft. runway gives you more options straight ahead

Airport environment: is there a parallel or intersecting runway that is more convenient to turn towards?

Surrounding terrain: are there any good options besides the airport or conversely, are there any obstacles to avoid?

Wind: I like to turn into the wind when possible since this requires a less aggressive turn to be lined up on final

Ceiling and visibility: do we need to set up any avionics to find our way back to the runway if it’s low IFR (synthetic vision helps a lot here)?

Lastly, we should consider that the human factor is an important piece of the puzzle, often left out during briefings. It's hard to predict how a pilot will react when faced with a serious emergency at a low altitude, but one thing is certain, your response will not be immediate. It will take you time to process the emergency, and you may even try troubleshooting (not that it's a bad idea, you should run an engine failure checklist if you have time). But, even taking a few seconds to troubleshoot could take away hundreds of feet of potential altitude. We hope this Safety Notice, will give a new insight to all pilots, and may be used towards your next flight.

Fly safe always.

Dr.Gema Goeyardi as a Gold Seal flight instructor will help you to achieve your dream as a pilot in a fast track accelerated program. His secret recipe of accelerated flight training syllabus has proven to graduate pilots from Private Pilot to ATP world wide in just very short days. As an ATP and Boeing 737 captain he always set a high standard of training and encouraged all students to have a professional pilot qualification standard. Lets talk with Dr.Gema for your training program plan, schedule your check ride, and customize your flexible training journey.

Dr.Gema Goeyardi as a Gold Seal flight instructor will help you to achieve your dream as a pilot in a fast track accelerated program. His secret recipe of accelerated flight training syllabus has proven to graduate pilots from Private Pilot to ATP world wide in just very short days. As an ATP and Boeing 737 captain he always set a high standard of training and encouraged all students to have a professional pilot qualification standard. Lets talk with Dr.Gema for your training program plan, schedule your check ride, and customize your flexible training journey.